Madonna – Live At FAC51 The Haçienda

Holiday

Burning Up

Factory Records Interview

The Factory Records All-Stars

‘She mesmerised the crowd – you knew there was a personality there’

t was one of those moments that lodge in the collective memory. The year was 1984, not exactly a high point of pop-culture history – the era of big hair, jazz-funk, Duran Duran, Dallas and Ghostbusters. It was late January; the time of year, recent research has confirmed, that we find more depressing than any other. It was Friday teatime, and the only thing to do, if you were young and into music, was to watch The Tube, the one rock show that had any credibility.

This edition, broadcast half from Newcastle as usual and half from the Hacienda club in Manchester, served up the familiar mish-mash of videos, amateurish interviews and live performances by earnest young people in baggy sweaters who appeared to have stumbled in from the students’ union. But then Jools Holland introduced someone different: female, American, focused, organised, poppy and dancey at the same time, a bundle of energy bursting out of the corner of the room, unknown but clearly going places. This was Britain’s first glimpse of Madonna before Like A Virgin or Desperately Seeking Susan, before Sean Penn and Guy Ritchie, Lourdes and Rocco, pointy bras and the Sex book, Vogue and Ray of Light, children’s books and Kabbalah, Live Aid and Live 8. For a whole generation, it was a moment they wouldn’t forget.

Madonna has never gone away since, and at 47 she is right here, right now: number one in the singles chart with Hung Up, number one in the albums as well with Confessions on a Dance Floor, back in the clubs to promote it, and back on the telly, with an hour to herself on Parkinson. Stardom is 50% stamina, and Madonna has outrun everyone else in the race. Hung Up is her 59th hit, and she’s not finished yet. To her other outstanding qualities – iconhood, girl power, self-reinvention, Nietzschean will and Darwinian fitness – we can now add longevity.

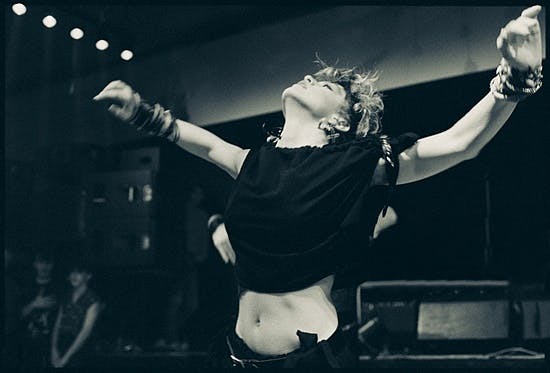

And it all began with that slot on The Tube, when she danced and mimed to Burning Up and Holiday. It’s an occasion that has passed into folklore. Online, it is referred to as “legendary”, and a site called www.madonnalicious.com has a clip for those who want to check out Madonna’s look – black cropped vest, black sawn-off leggings, black ra-ra skirt, a spray of wavy hair, big crucifix earrings, and a bare navel – a more clubby version of your basic 80s dance-studio look, not as embarrassing as it might have been, but not half as sharp as the stylised version of 80s disco chic that she has adopted now.

Madonna’s performance is remembered, and so is the fact that the show came from the Hacienda, later demolished, replaced by a block of luxury flats, and immortalised in the film 24 Hour Party People, which re-created this edition of The Tube. But to watch the original programme is to find that there was a lot more to it. It is a little time capsule, containing a slice of pop and media life.

The first thing Jools Holland does as he enters the Hacienda is greet two older people who are standing there looking unfashionably smart. One is Pat Phoenix, who as Elsie Tanner in Coronation Street was Manchester royalty. The other is the man Phoenix was to marry just before her death from lung cancer in 1986: Tony Booth, actor, father of Cherie and father-in-law of Tony Blair. Somehow, Booth manages to make a political point. He says he has read that there is a link between cancer and blue-veined cheese, and wonders why the government hasn’t done anything about it. The fact that he is puffing on a cigarette just adds to the surrealism.

In retrospect, Madonna is much the biggest name on the bill, but at the time, her first hit, Holiday, had only scratched the charts. She seems to have been a late addition to the line-up: her name doesn’t appear on the ticket. Malcolm Gerrie, executive producer of The Tube, has been quoted as saying that the show paid for her to travel to Manchester because her record company, Warner Brothers, didn’t see her as “a priority artist”. She found herself sharing the floor with a bunch of acts heavily skewed towards Factory Records, the zeitgeisty Manchester label that owned the Hacienda. The programme is basically Madge and the Mancs.

Top of the bill were the Factory All Stars, a scratch group featuring members of various bands including the Durutti Column, Quando Quango and the pioneering punk-funk group A Certain Ratio. Also performing were Britain’s first breakdance troupe, Broken Glass, who included the rapper Kermit, later to join Black Grape. On a crowded stage, the best-known figures were Bernard Sumner and Stephen Morris, then, as now, members of New Order, who have shown as much staying power as Madonna, albeit not at the same wattage.

The only individual named on the ticket was Marcel King, a Manchester soul singer with a beautiful voice. He had been the frontman for Sweet Sensation, a teenage soul band who made their name on the talent show New Faces, the mid-70s precursor of Pop Idol. Tony Hatch, the songwriter and Simon Cowell of the day, wrote a song for them, Sad Sweet Dreamer, which went to number one in 1974, but their bubble soon burst and, as a solo artist, Marcel King achieved more acclaim than sales. He died in 1995, aged 38, of a cerebral haemorrhage. The tragedy deepened two years later when his son Zeus, 19, was shot dead in an outbreak of gang warfare in south Manchester. Marcel King’s signature song, Reach for Love, is available on iTunes.

Among the interviewees on the programme was Morrissey, who, like Madonna, was just taking off. Asked a series of questions that are duff even by The Tube’s standards, Morrissey responds with magnificent hauteur. The Smiths’ debut album is out shortly, he says, “and I expect the highest of critical acclaim because it’s very, very good”. He also pours scorn on the rock video: “I think it’s going to die very quickly.”

Madonna herself doesn’t remember that day at the Hacienda. Tony Wilson, Factory’s boss, met her years later and told her she had played at his club. “She gave me an ice-cold stare,” he told the Manchester Evening News, and said, ‘My memory seems to have wiped that.’ ” But that hasn’t happened to everybody who was there that day.

Norman Cook

DJ, remixer and pop star who has had several chart-topping incarnations, first as a member of the Housemartins (under the name Quentin Cook), then as Beats International, and more recently as Fatboy Slim.

“I was in the audience, you can see me about twice.see me about twice. I was invited by Kermit to see the filming. It was probably the first time I’d ever been to Manchester. This was pre-Housemartins: I was 21, at Brighton Polytechnic, DJing a bit. I wasn’t Norman then, I was Quentox: The Ox That Rocks!

“Madonna was pretty much unknown at that point. I’d seen a couple of pictures of her in The Face, on the grounds that she was Jellybean Benitez’s girlfriend. There were so many bands on, there was a kind of communal dressing room, all the bands were hanging about and there was this tiny little American girl, looking pretty foxy. She caught your eye. Kermit and the boys started talking to her: “Who are you?” – “I”m Madonna.” She was really friendly, very affable. You have to be affable when you’re on the bottom rung.

“She said, “You’ve got to come and give us some support,” so we were down the front. She wasn’t on the stage, just on the dance floor. Singing? Nah, I doubt it. She danced like Cliff Richard with hips – two arms in the air, the “power to all our friends” dance, but with much hip movement. She mesmerised the crowd. She won a huge number of friends that day. You figured there was a personality there, it wasn’t just a faceless dance record. That one performance might have been the thing that broke her in England, maybe not on the pop scene but as a dance artist.

“Her career has had highs and lows, she’s done some great tracks and a couple of stinkers. One thing I’ll say for her, she’s really brave in her choice of producers – people like Stuart [Price, with whom she worked on her current album], and Mirwais, who are mavericks. She knows her onions and she’s prepared to take a risk.

“I’ve been asked to remix her a few times. She asked me to do Ray of Light. I did speak to her on the phone about that – I said it just wasn’t my sort of song. She got Sasha to do that and it worked brilliantly. The worst thing about that day at the Hacienda was that the mate I went up with was a photographer, and I could have had my picture taken with Madonna in her full string vest. But I didn’t.”

Martin Moscrop

Guitarist and trumpeter with A Certain Ratio. On the film 24 Hour Party People, he was in charge of getting the cast to look and sound like rock musicians.

“I remember thinking, “Ah, she’s coming over here now, is she?” We had come across her in New York, in 1982. We were playing Danceteria and she was the support. Her manager paid $100 to add her to the bill. I think it was her first ever gig. You could sense she was going to be big – she was just bossing everyone around. It was very last-minute, and when she got there we were finishing the soundcheck. When you’re the main band, you don’t move any gear, the support has to fit in round it. But she started to move our gear to make room for her dancers. So we said in our Mancunian accents, “Fook off.” We didn’t move the gear.

Greg Wilson

Resident DJ in the early days of the Hacienda who drew black audiences by playing electro-funk ahead of its time. Quit in 1983 to manage Broken Glass.

“People didn’t know who Madonna was. A lot of the crowd were a bit bemused by it all. She was working hard, but the Hacienda crowd wasn’t a dance audience at the time so what she was doing, with two male dancers, wouldn’t have been what they were into.

“I was in the dressing room with a dozen guys from Broken Glass. They were chatting away with her. There was a certain point where she seemed quite moody. The people from the Hacienda were scurrying around. There’s a story that they offered her £50 to perform again later that evening, but I can’t see that. Everything suggested to me that they thought she was really special; they seemed to be running around after her, treating her as the star.”