During recent times I’ve been intrigued to hear about the growing schism on the House scene here in the UK, brought about by the introduction, primarily by young black dancers, of ‘foot shuffling’ (aka ‘cutting shapes’), an increasingly popular style of dancing that has been met with much hostility in certain quarters, and, somewhat bizarrely, resulted in shufflers being banned from some clubs for dancing in this way. The accusation is that not only do they take up too much dancefloor space, but there’s a general ‘moodiness’ with regards to their attitude. Although it no longer seems to be online, there was even an ‘Anti Foot Shuffling Campaign’ page on Facebook, with some of the posts suggesting underlying issues of racism. As one person commented, “It’s not that all these people on here hate shufflers, they just don’t like fact that black people are into House music now.” Although this comment may be well intentioned, it’s also somewhat misguided given there are, and always have been, plenty of black people in the UK who are big into House – it’s just that their presence is usually to be found away from the mainstream, in more specialist avenues like the Deep and Soulful House scenes. Furthermore, some of the older black crowd are also resistant to this new wave of shuffling, so to present it as a purely black / white issue would be wrong.

That said, what’s clear from this whole kerfuffle is that there are a significant amount of mainly white enthusiasts on the scene today who seem to segregate House as somehow belonging to them, whilst suggesting the black crowd should stick to ‘their own music’, the likes of Grime, Hip Hop, R&B and other more ‘urban’ genres. This is all despite the fact that House, as anyone with even a basic awareness of its origins would tell you, was born within Chicago’s black clubbing community back in the mid-’80s.

The 25th anniversary of the Acid House ‘Second Summer Of Love’ is upon us (the original ‘Summer Of Love’, of course, being way back in psychedelic ’67, emanating from the Hippie movement of San Francisco). It’s remarkable that House music has been the main staple of British dancefloors for a colossal quarter of a century, the original ‘ravers’ now middle-aged. Yet despite its importance to this country’s popular culture, its true roots have never been fully acknowledged. In fact, if you told many of those on the House scene today that it was mainly black kids in the UK who first embraced the music, they’d no doubt look at you incredulously, for everybody knows that Ibiza ’87 was year zero, as this is how the story has, and continues to be told – the true origins in the relatively grim cities of the North and Midlands buried deep beneath the sun-drenched romance of the White Isle.

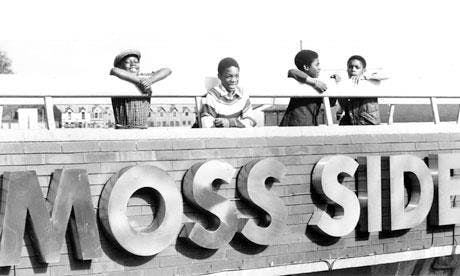

What’s even more remarkable is that the original style of dancing to House music in this country, before the hands in the air approach of the Rave era, was uncannily similar to shuffling, as illustrated by this now historic video, recorded at the Moss Side Community Centre in Manchester on September 27th 1986:

When it was originally uploaded, the title chosen for this clip, ‘Mastermind Roadshow in Moss Side’, was somewhat misleading. Although Mastermind, the influential London DJ collective who were responsible for mixing most of the seminal ‘Street Sounds Electro’ compilations, did indeed appear that night, the DJ playing in this clip is none other than Mike Shaft, the legendary Soul & Funk specialist who graced the Manchester airwaves, his mid-Atlantic microphone style unmistakeable. Most importantly it includes a routine from Foot Patrol who adapted the Jazz-Fusion style of dancing to early House – in this respect they may well be described as prototype foot shufflers.

I was initially made aware of this clip via the Deep House and Techno producer Tony Lionni. It was amazing to see this room jam-packed with black kids, some of whom I knew personally, getting down to House music before, as many commentators would have you believe, the genre had made any real impact here – Ibiza ’87 still almost a year away. It was a real anthropological find, and a longer version of the footage can be viewed here on the Soul Control website.

This is something I’d been mocked for in certain circles for stating as fact, so to see my words validated via these momentous moving images was so much more than I could have hoped for – the proof being very much in the pudding, so to speak. A couple of years earlier I was frantically searching, without success, for a photograph to visually back up my attestation that it was the black crowd in Manchester who were responsible for bringing dance music to the fore at The Haçienda during the mid-’80s, when it had previously been regarded as an alternative / indie stronghold. People rarely took snapshots in clubs back then, but The Guardian, who were interested in running the piece (to be written by Marc Rowlands), insisted on photographic evidence before it was commissioned. The best I could come up with was Ian Tilton’s classic shot of Manchester dance troupe Foot Patrol performing at The Haçienda, but it was an image of regular clubbers they wanted, and, frustratingly, as this couldn’t be provided the article was shelved.

Foot Patrol can lay claim to being the original House music foot shufflers (although some people nowadays look across the world to cite Australia and ‘The Melbourne Shuffle’ as the starting point in the late ’80s), their style is traceable back to the Jazz-Funk scene of the late ’70s / early ’80s, and the ‘fusion crews’ that challenged each other (it was from these crews that many of the UK’s archetypal breakdancers emerged, having already developed the athleticism to attempt the dynamic moves demanded). Hewan Clarke, a Jazz aficionado, would become the original Haçienda DJ before returning to the black scene, where he helped facilitate the House movement in embryo (along with, most notably, the hugely influential Colin Curtis – who’d previously been a pivotal DJ on both the Northern Soul and Jazz-Funk scenes – as well as Piccadilly Radio Dance music presenter, Stu Allan, who was responsible for championing House music on the North-West airwaves, greatly widening its popularity in the process). Hewan recalls how it all evolved;

“Samson and his crew (Foot Patrol as they’d come to be known) would travel all over the country. They’d go to Birmingham. They’d go to clubs in Nottingham, Leeds, Derby, all the happening places. They’d be picking up a lot of styles from clubs and bringing them back to Manchester. These guys were very innovative in terms of the way they were moving on the floor, because the way you move on the floor depicts the type of music that’s played to keep you moving like that. So, this new music was coming out. We knew you couldn’t dance to it the old way we used to dance to Jazz, Funk and Soul and stuff, and it was people like Samson that brought this new dance in and it really hit a vein amongst a young group of dancers at the time and people like myself. We looked at them, saw the way they were dancing and that was how the whole House thing developed.”

But why was it the North and the Midlands at the vanguard when it came to the emergence of House (also then known as Garage, in reference to the type of music you might hear at NYC’s famous Paradise Garage) in the UK?

Firstly I should explain what was meant by ‘the black scene’, as it was referred to back then. As the name suggests, this is where you’d find black kids dancing to the most cutting-edge music of the time, alongside the more adventurous white kids, who unified with their black brethren during what was still an overtly racist time, to transcend this divisive era via a love of music. The passion of this scene can’t be understated, with many people, amidst Thatcher’s Britain, on the dole with little prospect of work, yet thinking nothing of travelling 50, even 100 miles, to hear what they considered the most upfront music available – the majority of it fresh in on import from the US. They’d make sure that they were at the top club nights and All-Dayers, literally by hook or by crook – it was that fundamental to their existence.

What should be taken into account is that there was a definite North / South divide pre-Rave, with very little crossover between the DJs – Southern DJs rarely played up North and vice-versa. This led to differences in emphasis, and, during the mid-’80s, things had moved in contrasting directions. In London the Rare Groove scene held sway, and the illegal warehouse parties of this period would lay the foundations for the Rave events that followed later in the decade – Rare Groove set the environment. This was, once again, black led, with DJ Norman Jay at the heart of things. It was very much a London movement, which, as huge as it was in the capitol, never really gained a foothold in the main black music strongholds of the North and Midlands at the time – Birmingham, Nottingham, Sheffield, Huddersfield, Leeds and, of course, Manchester. There was much interconnectivity between these cities, and this had its origins in the All-Dayer scene, dating back to the Jazz-Funk era. So, whilst London chimed to Rare Groove and Boogie, the North and Midlands continued the more Electro geared direction that had defined the early ’80s, with House (before it was referred to as such) initially regarded as a rhythmically straighter take on Electro, out of Chicago rather than New York. This was the arena in which the early Trax and DJ International releases first found favour on this side of the Atlantic – supplemented by the Hip Hop and Street Soul flavours of the time on the specialist scene.

This is not to say that there weren’t DJs in London championing House at this point. Jazzy M is often cited as one of the UK pioneers, alongside names like Noel & Maurice Watson, Colin Faver, Eddie Richards and Mark Moore (the latter 3 responsible for exposing House to an influential mixed gay audience, unconnected to the Hi-NRG scene, some of whom, coincidently, were taking Ecstasy pre-Ibiza). Hosting ‘The Jacking Zone’ on London Pirate station LWR, as well as running the record shop, Vinyl Zone, Jazzy M was evangelical in his support of House, but initially found it a hard slog to get the music he loved taken seriously down South. He remembered;

“Though they’d started playing it in Manchester, most of London was still caught up in that Rare Groove and Hip Hop thing. A lot of people were saying to me ‘why are you playing this Hi-NRG’ and it was hard work but people were starting to get into it.”

The Manchester clubs that sparked things off were The Playpen, The Gallery, Legend and Berlin, with Colin Curtis, Hewan Clarke and Stu Allan at the forefront of things. Allan also wielded huge power via his weekly radio show, which was broadcast to a vast amount of people throughout the region every Sunday (Piccadilly being one of the UK’s most popular local radio stations). Laurent Garnier, not yet a DJ, but in the North-West of England working as a chef at the time, recalls the trouble he had obtaining a copy of Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk’s ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ (a record that would subsequently make the UK Top 10, the first House hit), when it first came in on import in ’86;

“I was living half an hour from Manchester, and there was a shop called Spin Inn. You had to call them to make sure they’d save the records for you, because they’d only have five copies of each and it wasn’t sure if you could get them. With ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’, it took me months to finally get a copy. And of course to hear the songs this DJ, Stu Allan, was on the radio in Manchester and I was listening to his show and taping the show.”

At The Haçienda, Mike Pickering (then partnered by Martin Prendergast), was on a roll, his Nude night on a Friday really gaining momentum, with major representation from Manchester’s black strongholds of Hulme and Moss Side, the audience “fifty percent black, fifty percent white”, and attracting some serious dancers in the process. Graham Massey, later of 808 State, recalled; “Friday nights were a lot more black, yet much more to my taste in the jazzy area…people that took dancing seriously in that jazz dancing kind of way”. Pickering was soon to become a central figure in the House music story – as he tells it, “a young kid from Moss Side” handed him his first House record, ‘No Way Back’ by Adonis (1986), and when he played it “the club went crazy”. Adonis, along with Latin Jazz and Salsa musician, Tito Puente, provided the inspiration for ‘Carino’ by T-Coy (1987), the first UK House track to make a national impact, courtesy of Pickering and Simon Topping (previously members of Factory Records band Quando Quango) in collaboration with the late keyboardist, Richie Close (the track crucially supported by Stu Allan on his radio show, and later Coldcut on Kiss FM in London). Foot Patrol (also 2 other local crews, the She Devils and Fusion Beats) were featured in the promo video:

Elsewhere, DJ’s like Graeme Park at The Garage in Nottingham and Winston & Parrot at Jive Turkey in Sheffield were starting to have a big influence in those cities (they would also combine for a series of memorable ‘The Steamer’ nights at Sheffield’s Leadmill). Park would eventually come across to The Haçienda in 1988, hooking up with Mike Pickering to form one of the most celebrated DJ partnerships of all;

“obviously I knew Mike cos we were doing a very similar thing. I went to The Haçienda and couldn’t believe what I saw because obviously it was three times as big as what I was doing in Nottingham and a real kinda mix, a lot of black faces there”.

Completing the trinity of Haçienda House specialists was Jon DaSilva, and everything was now in place for the venue to become the most important club for the furtherance of House music, not only in the UK, but the world.

Later down the line, when the documentation of the House / Rave scene went into overdrive, with the Ibiza story overriding everything that had gone before, I couldn’t help but regard it as a whitewashing of black culture in this country. I was no longer directly involved with the club scene at this point, just watching events unfold from the sidelines, so my hope was that someone would come along to set the record straight – but it didn’t happen. Article after article, then book after book began to appear, but there was always this great glaring omission with regards to how things had originally flourished via the black scene. Although it often felt as though the sinister undertones of cultural racism were at play, I came to realise that the writers simply weren’t aware of what had happened because they were never a part of the black scene – most had only got into dance music with the advent of Acid House and Ecstasy, so had no personal knowledge of the black clubs that had led the way. Instead of making the proper connection to what had gone before, they generally took the easy, more romantic option, making Ibiza ’87 their starting point, and thus creating a mythology that persists to this day.

I could quote from a selection of books, documentaries and articles, showing how this misinformation has perpetuated down the years – and not just by those writing about dance culture, but consequently music documentarians working in a wider context. Only recently I was enjoying the highly informative ’33 Revolutions Per Minute’ (2010) by Dorian Lynskey, a book that outlines the history of the protest song. There’s a chapter about Rave culture, and the more political messages contained in the music, but it also endorses the myth I’ve been talking about, authoritatively stating that; ‘The DJs who brought House and Techno to Britain did so via the sun-kissed idyll of Ibiza’. When I come across this type of error, it makes me question what else in the book might be inaccurate, but in this case I can’t be too critical of the author – he’s only repeating what has been presented as fact so many times by people purported to be dance music experts. If the specialists can’t get it right, what hope for those who are dependent on the authenticity of these specialists.

Most people couldn’t care less about origins and lineage – they like the music, but don’t want to study it. However, there are always a significant minority whose love of music, or a particular genre of music, creates enough fascination in them to want to explore its roots and branches. Unfortunately there’s precious little in print that enables even students of dance culture access to the full picture, allowing them to make a balanced assessment of why things worked out the way they did.

By omitting the Black British contribution to our culture we hide the fullness of its riches, and know less about ourselves as a consequence (regardless of our personal ethnicity). It’s an inspirational story that needs to be known, in order to serve the future – culture is all about connections and fusions, previously separate aspects coming together to create a new expression, and this is exactly what happened in Britain with the black / white mix of ideas and identity that shaped (and continues to shape) the course of popular culture in this country.

Gerald Simpson (aka A Guy Called Gerald) provides the perfect analogy for what happened in Manchester. Most people would assume that he went to The Haçienda, heard this incredible House music for the first time, had an epiphany, and then went home and set to work on the era defining single ‘Voodoo Ray’ (which he wrote with Foot Machine in mind, visualising how they might dance to it). The reality, of course, is that Gerald and his contemporaries were those very kids from Hulme and Moss Side, who brought House music into The Haçienda in the first place. Gerald had already been on the black scene for many years, dancing to Jazz-Funk, then Electro, before starting out with the Scratch Beatmasters as a Hip Hop DJ (MC Tunes rapping). ‘Voodoo Ray’ isn’t an orthodox House track, but a culmination of his influences – The Haçienda providing the perfect setting in which to unleash this quintessential British dance track. Inadvertently bestowing Gerald with his name was Stu Allan – prior to ‘Voodoo Ray’, on playing a track he’d been given on tape by a local newcomer, he told his Piccadilly listeners that it was by a guy called Gerald from Hulme.

Whilst Ibiza and its Balearic spirit would mark a seismic shift for British dance culture, this had more to do with resultant emergence of the drug Ecstasy within British clubland than the House music of Chicago – House, as illustrated, having already become a key component of underground dance culture well before DJs Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling, Nicky Holloway and Johnny Walker made that fateful trip to visit their friend and fellow DJ, Trevor Fung, in the summer of ’87 (Fung, who lived on the island at the time, has found himself increasingly marginalised within the story as the years pass, despite the fact that it was his pioneering spirit that brought the others out there in the first place). It’s a tale that, even from its inception, generated a life of its own, re-writing history as the past was largely eclipsed and, to paraphrase a popular track of the period, Everything, seemingly, began with an E. Graeme Park saw it as the South grabbing the spotlight, having originally been beaten to the punch where House was concerned;

“I mean me and Mike Pickering never went to Ibiza but we had a massive scene. That was just that London thing of ‘we invented everything’, y’know? I really do think that.”

Some people may rightfully point out that, if there was such a major black influence on what happened at The Haçienda, why are black people clearly in the minority in the photos and video footage of the club at the height of its fame? The answer is that when the whole thing blew up in 1988, and legions of E’d up white kids, most of whom previously had little affinity with dance music, staked their claim to its ‘discovery’, the blacks, who regarded this as their space, their precious dancing space, being invaded, gradually moved on (Konspiracy, with DJs like the Jam MC’s, Nick Grayson, Justin Robertson and Greg Fenton, subsequently becoming their club of choice before the police closed it down, with the black presence in the city centre clubs rapidly decreasing as a consequence). Mike Pickering believes the influx of ecstasy was a factor with the black audience, most of whom were purely herbal in their choice of highs;

“I think the drugs put them off, because they didn’t take them in those days”.

Colin Curtis echoed this opinion;

“most of the black guys, that I knew anyway, didn’t take that particular drug…they didn’t need to, they came to dance, it was about the dance, the chilling afterwards was a different party”.

However, Mike Pickering believed that the invasion of their dancefloor space was the defining aspect;

“I likened it to the Mexican wave coming across the club. Everyone was doing the same dance and there was no room. The black dancers didn’t dig that.”

It’s ironic to think that today’s foot shufflers are criticised for the very thing that made the black dancers desert The Haçienda in their droves – wanting to express themselves on the dancefloor, without being confined to hands in the air standing room only. The dance of the ravers wasn’t about footwork, but arm and hip movements, the feet pretty much rooted to the same spot, which was never going to satisfy the physicality of those who’d graduated from the school of Fusion, where the feet did the talking, and cutting shapes didn’t mean ‘big box little box’ type moves.

Laurent Garnier, who’d been summoned back to France in 1988 for his national service, expressed his surprise on finding, when he later returned to Manchester, that the black crowd had largely moved on from The Haçienda. With the audience now predominantly white, and House music playing all night long, Mike Pickering, even as The Haçienda was gaining universal acclaim, began to have reservations;

“I regretted the fact that once you’d come down off the E everything was pure House…I could tell even in 1989 that that wasn’t a good thing and that what we were doing before was much more precious, because we were playing a wider range of music. By 1989 we were slaves to the beat.”

Acid House and its drug associations resulted in a full scale media frenzy, not least in the pages of The Sun, which, whilst rallying against the evils of Ecstasy, only served to further popularise the movement with the younger generation. All of a sudden, people who’d previously had little affinity with dance music were popping pills and swamping the dancefloor. House was the soundtrack, and whilst it remained very much underground in its country of origin, it became something of a mainstream obsession in Britain – everyone, it seemed, wanted to join the dance.

House music, supplemented by MDMA, would, of course, go on to dominate the dance landscape in the UK throughout the coming decades, but for many people who were there at the start, something had been lost. Deep House would retain the connection to the black scene, but black people became but a small minority when it came to the overall House demographic in Britain, and indeed Europe, more likely to be found dancing to urban flavours in the Cypriot resort of Ayia Napa than raving in Ibiza.

What’s sad is that black and white generally separated following the Acid House explosion, whereas, throughout the ’80s, there was a real meeting of minds, and it was this very coming together that created the conditions for a club like The Haçienda to flourish in the first place – the black kids from areas like Hulme and Moss Side interacting with the students and Indie enthusiasts who’d made up the venue’s original audience, to place Manchester right at the centre of worldwide dance culture during that heady late 80’s into early 90’s period.

Despite the separation on the House side of things (or perhaps because of it) British black music would flourish in the post-Rave period. Taking the essence of Rave, but adding the breakbeats of Hip Hop, whilst underpinning this with the Bass culture of Jamaican heritage, they would create their own new directions, beginning with Hardcore, before morphing into Jungle, Drum & Bass, UK Garage and, as a new century dawned, onwards into Grime and beyond. No longer was black music in the UK regarded as simply a pale imitation of the real deal from the US and JA (which was a bit harsh on some of the wonderful pre-Rave British black / dance releases), but a hybrid style all of its own, influenced by America and Jamaica, but infused with a unique home grown sensibility.

With regards to the cutting of shapes, Tim Lawrence hit the nail on the head when he made the comparison between the two distinct ways of dancing to House, pre and post-Ecstasy. He pointed out that “black social dance created space for individual expression within collective movement”, whereas the ravers “generated a wave of bliss in which the euphoria of the crowd all but drowned out the individual”.

Whilst I understand the appeal of the communal experience, and the sense of belonging that can go with it, I don’t think that this should be at the expense of individual expression, especially now, at a time when, to vast swathes of clubbers, community has been reduced to bobbing up and down on the spot, facing the same way as everyone else (towards the DJ), with a fist pumping high, or worse still, a mobile phone raised aloft. Speaking for myself, there’s nothing I like to see more than a dancefloor where people are facing each other, not me, whilst grooving away to the tunes I play as they give it up and get down, immersing themselves in the moment by losing themselves in the music.

Isn’t that what it’s all about?